Your work spans several distinct, but overlapping areas of discourse. We could start by talking through design, animation, glitch art, code, game play or the interface. I want to start right from the bottom though, and ask you about inputs and outputs. A recent work you collaborated on with Jeff Thompson, You Have Been Blinded - “a non-visual adventure game” - takes me back to my childhood when playing a videogame often meant referring to badly sketched dungeon maps, before typing N S E or W on a clunky keyboard. Nostalgia certainly plays a part in You Have Been Blinded, but what else drives you to strip things back to their elements?

I’ve always been interested in how things are built. From computers to houses to rocks to software. What makes these things stand up? What makes them work? Naturally I’ve shifted to exploring how we construct experiences. How do we know? Each one of us has a wholly unique experience of… experience, of life.. When I was a kid I was always wondering what it was like to be any of the other kids at school. Or a kid in another country. What was it like to be my cat or any of the non-people things I came across each day? These sorts of questions have driven me to peel back experience and ask it some pointed questions. I don’t know that I’m really interested in the answers. I don’t think we could really know those answers, but I think it’s enough to ask the questions.

Stripping these things down to their elements shows you that no matter how hard you try, nothing you make will ever be perfect. There are always flaws and the evidence of failure to be found, no matter how small. I relish these failures.

Your ongoing artgame project, Writing Things We Can No Longer Read, revels in the state of apophenia, “the experience of seeing meaningful patterns or connections in random or meaningless data”. [1] The title invokes Walter Benjamin for me, who argued that before we read writing we “read what was never written” [2] in star constellations, communal dances, or the entrails of sacrificed animals. From a player’s point of view the surrealistic landscapes and disfigured interactions within your (not)(art)games certainly ask, even beg, to be interpreted. But, what role does apophenia have to play in the making of your work?

When I make stuff, I surround myself with lots of disparate media. Music, movies, TV shows, comics, books, games. All sorts of stuff gets thrown into the pot of my head and stews until it comes out. It might not actually come out in a recognizable form, but the associations are there.

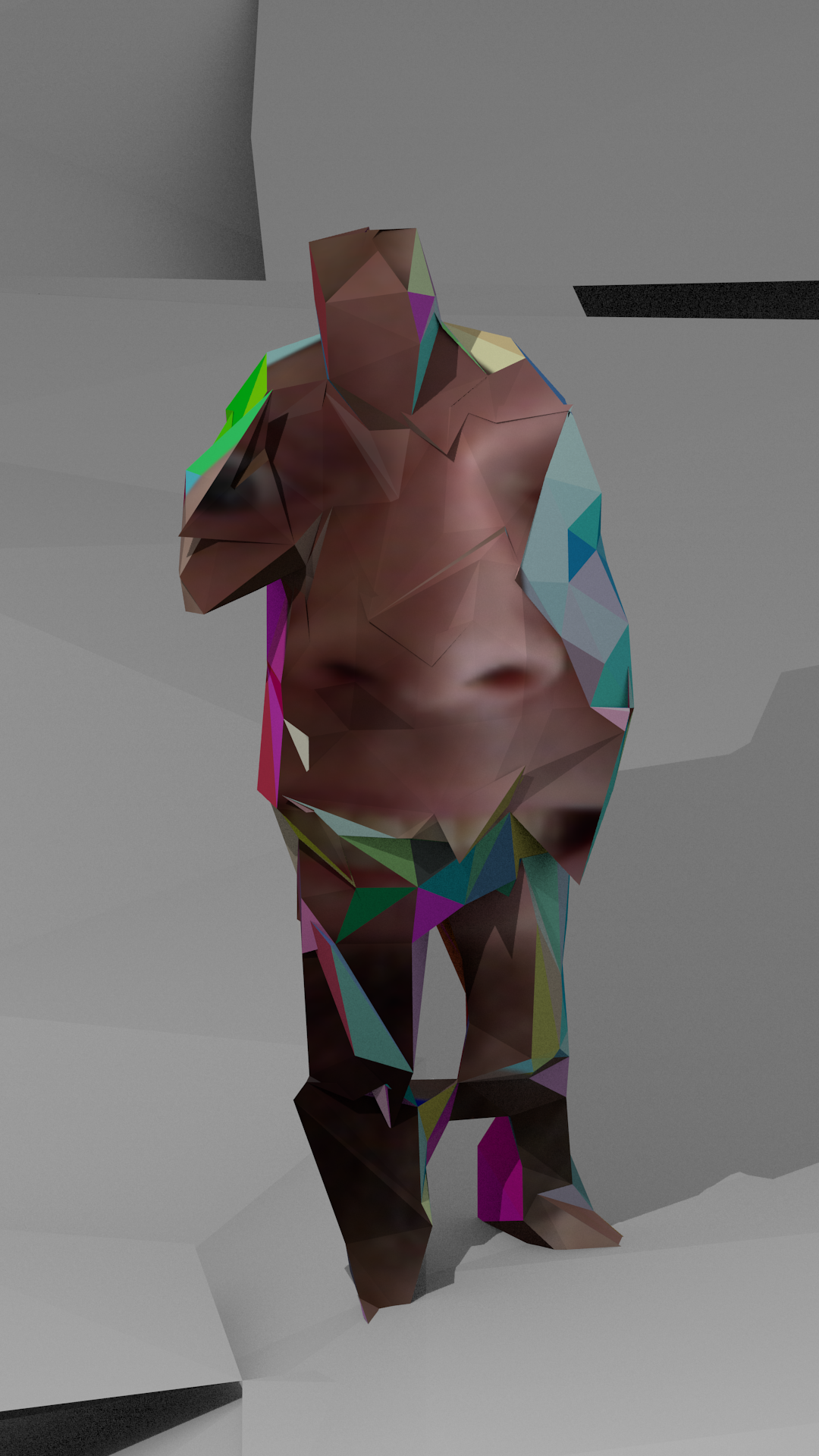

A specific example can be found in a lot of the models I use. I get most of them, or at least the seed of them, from open source models I find on 3D Warehouse. Because of the way that website works, it’s constantly showing you models it thinks are similar for whatever reason. Often I’ll follow those links and it will take me down symbolic paths that I never would have consciously decided to pursue. This allows a completely associative and emergent composition to take form.

I’d like to paraphrase and link up your last two answers, if I may. How do “relishing failures” and “allowing things to take form” overlap for you? I know you have connections with the GLI.TC/H community, for instance. But your notgames Me&You, Down&Up, and your recent work/proposition Make Me Something seem to invoke experiments, slips and disasters from a more oblique angle.

All are a means of encouraging surprise. In each piece it’s not about the skill involved, but about the thrill of the unknown. In all of my projects I try to construct a situation where I have very little control over the outcome. Glitch does this. But within the glitch community there’s a definite aesthetic involved. You can look at something and know that it’s glitch art. That’s not true for everything, but there is a baseline. For my notgames work I embrace the practice, not necessarily the look. I want irregularity. I want things to break. I want to be surprised.

Your work in progress, the Remeshed series, appears to be toying with another irregular logic, one you hinted at in your comments about “associative and emergent composition”; a logic that begins with the objects and works out. I hear an Object Oriented echo again in your work Make Me Something, where you align yourself more with the 3D objects produced than with the people who requested them. What can we learn from things, from objects? Has Remeshed pushed/allowed you to think beyond tools?

That’s a tricky question and I’m not sure I have a satisfactory answer. Both projects owe their existence to a human curatorial eye. But in both I relinquish a lot of control over the final object or experience. I do this in the spirit of ready-to-hand things. By making experiences and objects that break expectations our attention is focused upon them. They slam into the foreground and demand our attention. Remeshed, and to an extent, Make Me Something, allows me to focus less on the craft of modeling and animation and more on pushing what those two terms mean.

As Assistant Professor and Program Director of the Game Studies BSc atBellevue University you inevitably inhabit a position of authority for your students. Are there contradictions inherent in this status, especially when aiming to break design conventions, to glitch for creative and practical ends, and promote those same acts in your students? Yourecently modified Roland Barthes’ 1967 text ‘The Death of the Author’ to fit into a game criticism context. It makes me wonder whether “The Player-God” is something you are always looking to kill in yourself?

Absolutely. When teaching I try break down the relationship of authority as much as possible. I prefer to think of myself as a mentor, or guide, to the students. Helping them find the right path for themselves. Doing this from within a traditional pedagogical structure is difficult, but worthwhile. Or so I tell myself.

In terms of the Player-God, I think yes, I’m always trying to kill it. But at the same time, I’m trying to kill the Maker-God. There is no one place or source for a work. There’s no Truth. I reject the Platonic Ideal. Both maker and player are complicit in the act of the experience. Without either, the other wouldn’t exist.

Age: Somewhere in my third decade.

Location: The Land of Wind and Grass / The Void Between Chicago and Denver

How long have you been working creatively with technology? How did you start?

Oof, for as long as I can remember. When I was 13 I killed my first computer about 4 days after getting it. I was trying to change the textures in DOOM. I had no idea what I was doing.

Later, in college I was in a fairly traditional arts program learning to blow glass. At some point someone gave me a cheap Sony 8mm digital camcorder and I started filming weird things and incorporating the (terrible) video art into my glass sculptures.

After that I started making overly ambitious text adventures and playing around with generative text and speech synthesizers.

Describe your experience with the tools you use. How did you start using them? Where did you go to school? What did you study?

I use Unity and Blender primarily right now. They’re the natural evolution of what I was trying to do way back when I was using Hammer and Maya.

I did my MFA in Interactive Media and Environments at The Frank Mohr Institute in Groningen, NL. I started working in Hammer around this time making Gun-Game maps for Counter-Strike: Source. During the start of my second semester of grad school I suffered a horrible hard drive failure and lost all of my work. In a fit of depression I did pretty much nothing but play CS:S and drink beer for three months. At the end of that I made WINNING.

What traditional media do you use, if any? Do you think your work with traditional media relates to your work with technology?

I’m not sure how to answer this. About the most traditional thing I do anymore is make prints from the results of my digital tinkering. Object art doesn’t interest me much these days, but it definitely influenced how I first approached Non-Object art.

Are you involved in other creative or social activities (i.e. music, writing, activism, community organizing)?

I’m involved with a lot of local game developer and non-profit digital arts organizations.

What do you do for a living or what occupations have you held previously? Do you think this work relates to your art practice in a significant way?

I’m an Assistant Professor of Game Studies at Bellevue University. The job and my work are inexorably bound together. I enjoy teaching in a non-arts environment because I feel it affords me freedom and resources I wouldn’t otherwise have. I actually hate the idea of walled-disciplines in education. Everyone should learn from and collaborate with everyone else.

Who are your key artistic influences?

Mostly people I know: Jeff Thompson, Darius Kazemi, Rosa Menkman, THERON JACOBS

and some people I don’t know: Joseph Cornell, Theodor Seuss Geisel, Bosch, Brueghel the Elder, most of Vimeo.

Have you collaborated with anyone in the art community on a project? With whom, and on what?

Yes. Definitely.

Most recently I’ve been working with Jeff Thompson. We made You Have Been Blinded and Thrown into a Dungeon, a non-visual, haptic dungeon adventure. We’ve also been curating Games++ for the last two years.

Do you actively study art history?

Yep. I’m constantly looking at and referencing new and old art. I don’t limit it to art, though. I’m sick of art that references other art in a never ending strange loop. I try to cast my net further afield.

Do you read art criticism, philosophy, or critical theory? If so, which authors inspire you?

Definitely. In no particular order: Dr. Seuss, Alastair Reynolds, Alan Sondheim, Dan Abnett, Samuel Beckett, James Joyce, Stephen King, Margaret Atwood, Italo Calvino, Mother Goose, Jacques Lacan, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Carl Jung, H.P. Lovecraft, Jonathan Hickman, Brandon Graham, John Dewey, Umberto Eco... the list goes on and on.

Are there any issues around the production of, or the display/exhibition of new media art that you are concerned about?

I think we’ve partially reached an era of the ascendant non-object. That is, an art form, distinct from performance and theatre, that places an emphasis wholly on the experience and not on the uniqueness of the object. Because of this move away from a distinct singular form, there’s no place for it in the art market. Most artists that work this way live by other means. I teach. Others move freely between the worlds of art and design. Still others do other things.

The couple of times I’ve had solo exhibitions in Europe, I’ve almost always been offered a livable exhibition fee. Here in the States that’s never been the case. When I have shows stateside, I always take a loss. The organizer may cover my material costs, but there’s no way I could ever live off of it. Nor would I want to. I think the pressures of survival would limit my artistic output. I’m happier with a separation between survival and art.

[1] “Apophenia,” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopaedia, March 21, 2013, http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Apophenia&oldid=545047760.

[2] Walter Benjamin, “On the Mimetic Faculty,” in Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings (New York: Schoclen Books, 1933), 333–336.